Getting Started¶

The goal of this document is to help you get running quickly and with as little fuss as possible.

General guide¶

There are three main components (or processes) to consider when running huey:

- the producer(s), i.e. a web application

- the consumer(s), which executes jobs placed into the queue

- the queue where tasks are stored, e.g. Redis

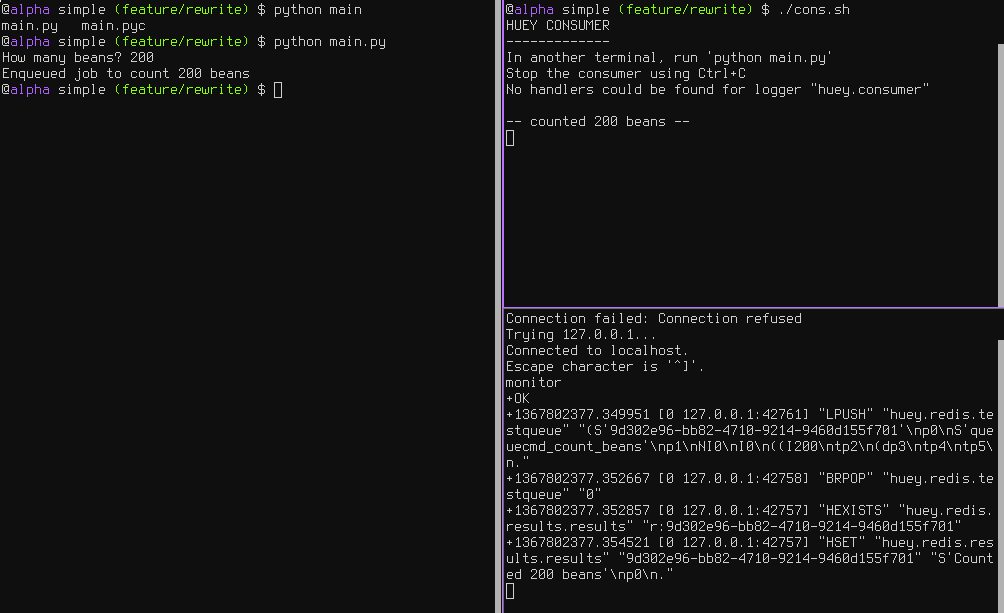

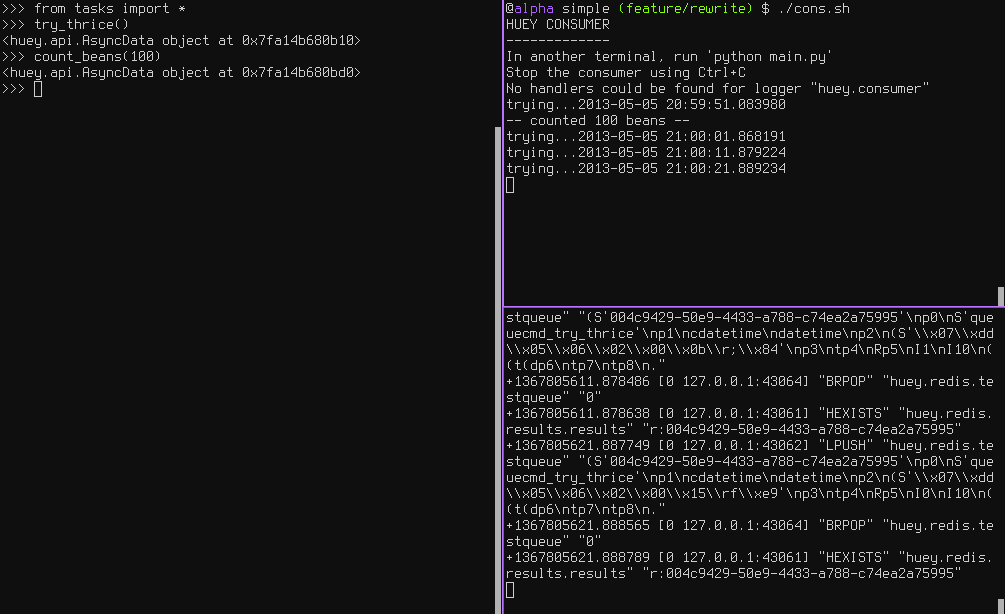

These three processes are shown in the screenshots that follow. The left-hand pane

shows the producer: a simple program that asks the user for input on how many

“beans” to count. In the top-right, the consumer is running. It is doing the

actual “computation”, for example printing the number of beans counted. In the

bottom-right is the queue, Redis in this example. We can see the tasks being

enqueued (LPUSH) and read (BRPOP) from the database.

Trying it out yourself¶

Assuming you’ve got huey installed, let’s look at the code from this example.

The first step is to configure your queue. The consumer needs to be pointed at

a Huey instance, which specifies which backend to use.

# config.py

from huey import Huey

from huey.backends.redis_backend import RedisBlockingQueue

queue = RedisBlockingQueue('test-queue', host='localhost', port=6379)

huey = Huey(queue)

The interesting parts of this configuration module are the Huey object

and the RedisBlockingQueue object. The queue is responsible for

storing and retrieving messages, and the huey is used by your application

code to coordinate function calls with a queue backend. We’ll see how the huey

is used when looking at the actual function responsible for counting beans:

# tasks.py

from config import huey # import the huey we instantiated in config.py

@huey.task()

def count_beans(num):

print '-- counted %s beans --' % num

The above example shows the API for writing “tasks” that are executed by the

queue consumer – simply decorate the code you want executed by the consumer

with the task() decorator and when it is called, the main

process will return immediately after enqueueing the function call.

The main executable is very simple. It imports both the configuration and the tasks - this is to ensure that when we run the consumer by pointing it at the configuration, the tasks are also imported and loaded into memory.

# main.py

from config import huey # import our "huey" object

from tasks import count_beans # import our task

if __name__ == '__main__':

beans = raw_input('How many beans? ')

count_beans(int(beans))

print 'Enqueued job to count %s beans' % beans

To run these scripts, follow these steps:

- Ensure you have Redis running locally

- Ensure you have installed huey

- Start the consumer:

huey_consumer.py main.huey(notice this is “main.huey” and not “config.huey”). - Run the main program:

python main.py

Getting results from jobs¶

The above example illustrates a “send and forget” approach, but what if your

application needs to do something with the results of a task? To get results

from your tasks, we’ll set up the RedisDataStore by adding the following

lines to the config.py module:

from huey import Huey

from huey.backends.redis_backend import RedisBlockingQueue

from huey.backends.redis_backend import RedisDataStore # ADD THIS LINE

queue = RedisBlockingQueue('test-queue', host='localhost', port=6379)

result_store = RedisDataStore('results', host='localhost', port=6379) # ADDED

huey = Huey(queue, result_store=result_store) # ADDED result store

We can actually shorten this code to:

from huey import RedisHuey

huey = RedisHuey('test-queue', host='localhost', port=6379)

To better illustrate getting results, we’ll also modify the tasks.py

module to return a string rather in addition to printing to stdout:

from config import huey

@huey.task()

def count_beans(num):

print '-- counted %s beans --' % num

return 'Counted %s beans' % num

We’re ready to fire up the consumer. Instead of simply executing the main program, though, we’ll start an interpreter and run the following:

>>> from main import count_beans

>>> res = count_beans(100)

>>> res # what is "res" ?

<huey.api.AsyncData object at 0xb7471a4c>

>>> res.get() # get the result of this task

'Counted 100 beans'

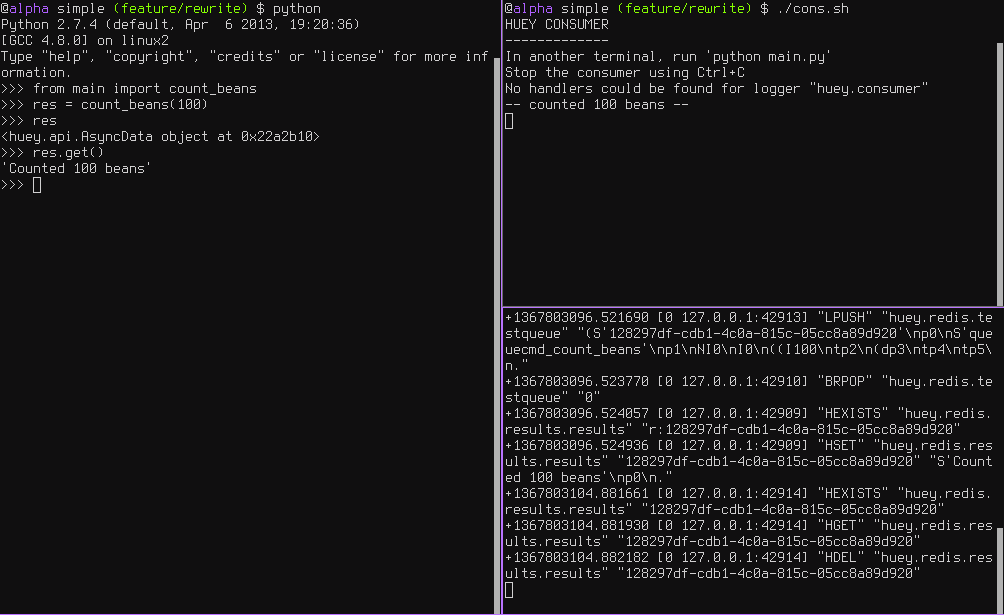

Following the same layout as our last example, here is a screenshot of the three main processes at work:

- Top-left, interpreter which produces a job then asks for the result

- Top-right, the consumer which runs the job and stores the result

- Bottom-right, the Redis database, which we can see is storing the results and then deleting them after they’ve been retrieved

Executing tasks in the future¶

It is often useful to enqueue a particular task to execute at some arbitrary time in the future, for example, mark a blog entry as published at a certain time.

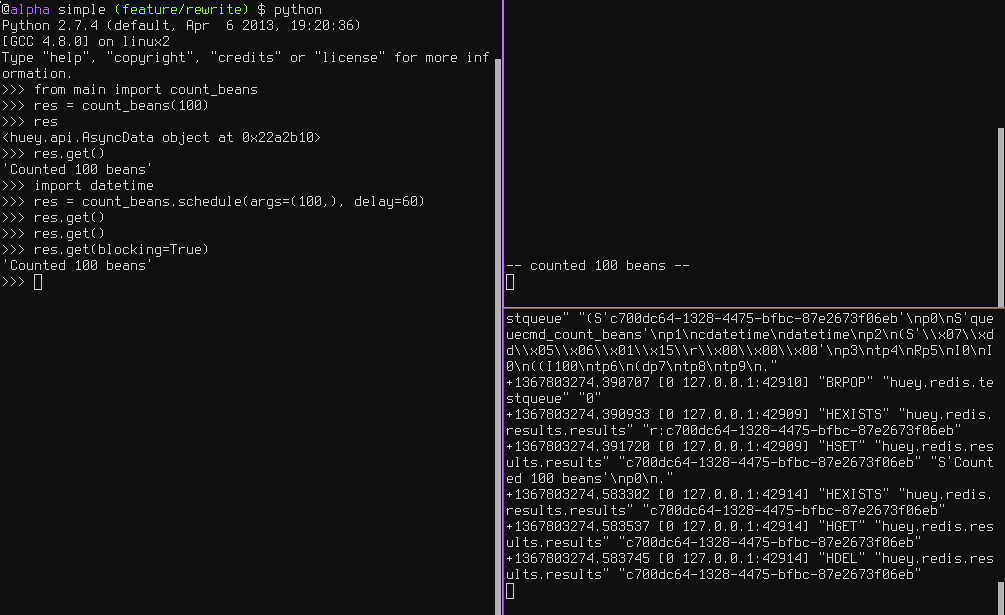

This is very simple to do with huey. Returning to the interpreter session from the last section, let’s schedule a bean counting to happen one minute in the future and see how huey handles it. Execute the following:

>>> import datetime

>>> res = count_beans.schedule(args=(100,), delay=60)

>>> res

<huey.api.AsyncData object at 0xb72915ec>

>>> res.get() # this returns None, no data is ready

>>> res.get() # still no data...

>>> res.get(blocking=True) # ok, let's just block until its ready

'Counted 100 beans'

You can specify an “estimated time of arrival” as well using datetimes:

>>> in_a_minute = datetime.datetime.now() + datetime.timedelta(seconds=60)

>>> res = count_beans.schedule(args=(100,), eta=in_a_minute)

Looking at the redis output, we see the following (simplified for reability):

+1325563365.910640 "LPUSH" count_beans(100)

+1325563365.911912 "BRPOP" wait for next job

+1325563365.912435 "HSET" store 'Counted 100 beans'

+1325563366.393236 "HGET" retrieve result from task

+1325563366.393464 "HDEL" delete result after reading

Here is a screenshot showing the same:

Retrying tasks that fail¶

Huey supports retrying tasks a finite number of times. If an exception is raised

during the execution of the task and retries have been specified, the task

will be re-queued and tried again, up to the number of retries specified.

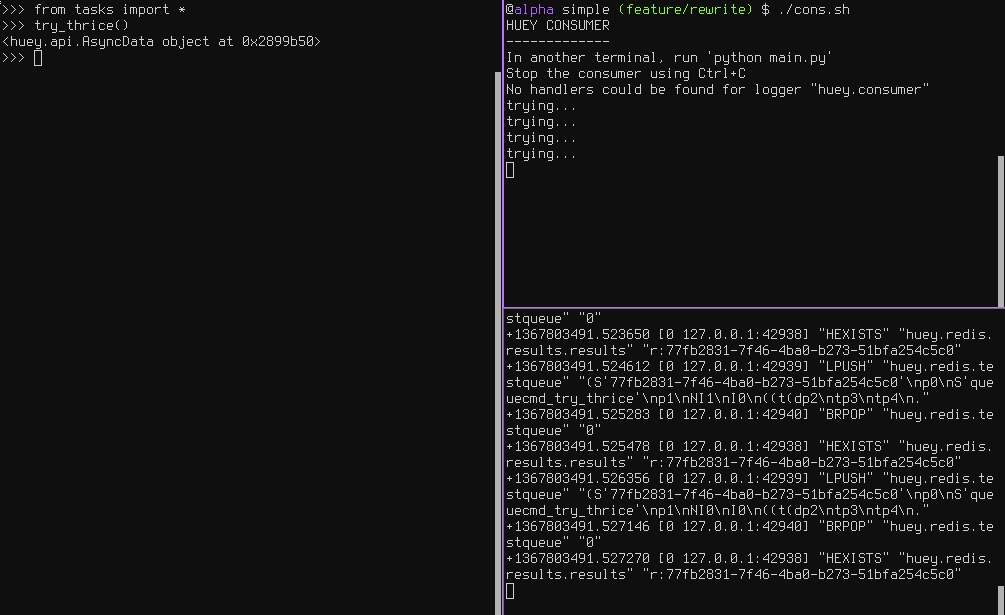

Here is a task that will be retried 3 times and will blow up every time:

# tasks.py

from config import huey

@huey.task()

def count_beans(num):

print '-- counted %s beans --' % num

return 'Counted %s beans' % num

@huey.task(retries=3)

def try_thrice():

print 'trying....'

raise Exception('nope')

The console output shows our task being called in the main interpreter session, and then when the consumer picks it up and executes it we see it failing and being retried:

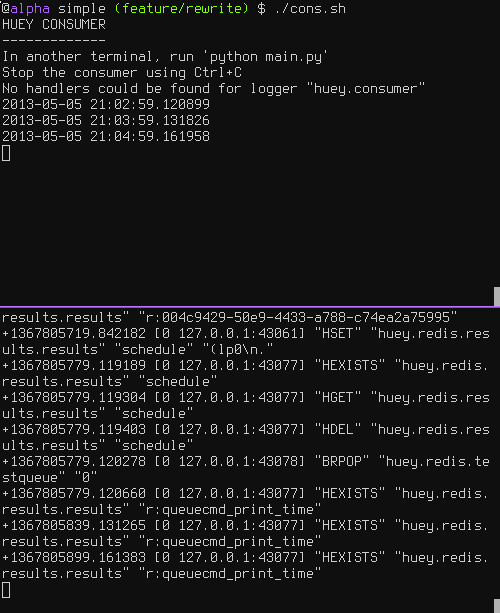

Oftentimes it is a good idea to wait a certain amount of time between retries. You can specify a delay between retries, in seconds, which is the minimum time before the task will be retried. Here we’ve modified the command to include a delay, and also to print the current time to show that its working.

# tasks.py

from datetime import datetime

from config import huey

@huey.task(retries=3, retry_delay=10)

def try_thrice():

print 'trying....%s' % datetime.now()

raise Exception('nope')

The console output below shows the task being retried, but in between retries I’ve also “counted some beans” – that gets executed normally, in between retries.

Executing tasks at regular intervals¶

The final usage pattern supported by huey is the execution of tasks at regular

intervals. This is modeled after crontab behavior, and even follows similar

syntax. Tasks run at regular intervals and should not return meaningful results, nor

should they accept any parameters.

Let’s add a new task that prints the time every minute – we’ll use this to test that the consumer is executing the tasks on schedule.

# tasks.py

from datetime import datetime

from huey import crontab

from config import huey

@huey.periodic_task(crontab(minute='*'))

def print_time():

print datetime.now()

Now, when we run the consumer it will start printing the time every minute:

Preventing tasks from executing¶

It is possible to prevent tasks from executing. This applies to normal tasks, tasks scheduled in the future, and periodic tasks.

Note

In order to “revoke” tasks you will need to specify a result_store

when instantiating your Huey object.

Canceling a normal task or one scheduled in the future¶

You can cancel a normal task provided the task has not started execution by the consumer:

# count some beans

res = count_beans(10000000)

# provided the command has not started executing yet, you can

# cancel it by calling revoke() on the AsyncData object

res.revoke()

The same applies to tasks that are scheduled in the future:

res = count_beans.schedule(args=(100000,), eta=in_the_future)

res.revoke()

# and you can actually change your mind and restore it, provided

# it has not already been "skipped" by the consumer

res.restore()

Canceling tasks that execute periodically¶

When we start dealing with periodic tasks, the options for revoking get a bit more interesting.

We’ll be using the print time command as an example:

@huey.task(crontab(minute='*'))

def print_time():

print datetime.now()

We can prevent a periodic task from executing on the next go-round:

# only prevent it from running once

print_time.revoke(revoke_once=True)

Since the above task executes every minute, what we will see is that the output will skip the next minute and then resume normally.

We can prevent a task from executing until a certain time:

# prevent printing time for 10 minutes

now = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

in_10 = now + datetime.timedelta(seconds=600)

print_time.revoke(revoke_until=in_10)

Note

Remember to use UTC if the consumer is using UTC.

Finally, we can prevent the task from running indefinitely:

# will not print time until we call revoke() again with

# different parameters or restore the task

print_time.revoke()

At any time we can restore the task and it will resume normal execution:

print_time.restore()

Reading more¶

That sums up the basic usage patterns of huey. Below are links for details on other aspects of the API:

Huey- responsible for coordinating executable tasks and queue backendstask()- decorator to indicate an executable taskperiodic_task()- decorator to indicate a task that executes at periodic intervalscrontab()- a function for defining what intervals to execute a periodic commandBaseQueue- the queue interface and writing your own backendsBaseDataStore- the simple data store used for results and schedule serialization

Also check out the notes on running the consumer.

Note

If you’re using Django, check out the django integration.