Consuming Tasks¶

To run the consumer, simply point it at the “import path” to your application’s

Huey instance. For example, here is how I run it on my blog:

huey_consumer.py blog.main.huey --logfile=../logs/huey.log

The concept of the “import path” has been the source of a few questions, but its actually quite simple. It is simply the dotted-path you might use if you were to try and import the “huey” object in the interactive interpreter:

>>> from blog.main import huey

You may run into trouble though when “blog” is not on your python-path. To work around this:

- Manually specify your pythonpath:

PYTHONPATH=/some/dir/:$PYTHONPATH huey_consumer.py blog.main.huey. - Run

huey_consumer.pyfrom the directory your config module is in. I use supervisord to manage my huey process, so I set thedirectoryto the root of my site. - Create a wrapper and hack

sys.path.

Warning

If you plan to use supervisord to manage your consumer process, be sure that you are running the consumer directly and without any intermediary shell scripts. Shell script wrappers interfere with supervisor’s ability to terminate and restart the consumer Python process. For discussion see GitHub issue 88.

Options for the consumer¶

The following table lists the options available for the consumer as well as their default values.

-l,--logfilePath to file used for logging. When a file is specified, by default Huey the logfile will grow indefinitely, so you may wish to configure a tool like

logrotate.Alternatively, you can attach your own handler to

huey.consumer.The default loglevel is

INFO.-v,--verboseVerbose logging (loglevel=DEBUG). If no logfile is specified and verbose is set, then the consumer will log to the console.

Note: due to conflicts, when using Django this option is renamed to use

-V,--huey-verbose.-q,--quiet- Minimal logging, only errors and their tracebacks will be logged.

-w,--workers- Number of worker threads/processes/greenlets, the default is

1but some applications may want to increase this number for greater throughput. Even if you have a small workload, you will typically want to increase this number to at least 2 just in case one worker gets tied up on a slow task. If you have a CPU-intensive workload, you may want to increase the number of workers to the number of CPU cores (or 2x CPU cores). Lastly, if you are using thegreenletworker type, you can easily run tens or hundreds of workers as they are extremely lightweight. -k,--worker-typeChoose the worker type,

thread,processorgreenlet. The default isthread.Depending on your workload, one worker type may perform better than the others:

- CPU heavy loads: use “process”. Python’s global interpreter lock prevents multiple threads from running simultaneously, so to leverage multiple CPU cores (and reduce thread contention) run each worker as a separate process.

- IO heavy loads: use “greenlet”. For example, tasks that crawl websites or which spend a lot of time waiting to read/write to a socket, will get a huge boost from using the greenlet worker model. Because greenlets are so cheap in terms of memory, you can easily run tens or hundreds of them.

- Anything else: use “thread”. You get the benefits of pre-emptive multi-tasking without the overhead of multiple processes. A safe choice and the default.

-n,--no-periodic- Indicate that this consumer process should not enqueue periodic tasks. If you do not plan on using the periodic task feature, feel free to use this option to save a few CPU cycles.

-d,--delay- When using a “polling”-type queue backend, the amount of time to wait between polling the backend. Default is 0.1 seconds. For example, when the consumer starts up it will begin polling every 0.1 seconds. If no tasks are found in the queue, it will multiply the current delay (0.1) by the backoff parameter. When a task is received, the polling interval will reset back to this value.

-m,--max-delay- The maximum amount of time to wait between polling, if using weighted backoff. Default is 10 seconds. If your huey consumer doesn’t see a lot of action, you can increase this number to reduce CPU usage and Redis traffic.

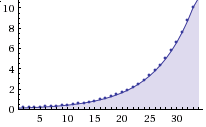

-b,--backoffThe amount to back-off when polling for results. Must be greater than one. Default is 1.15. This parameter controls the rate at which the interval increases after successive attempts return no tasks. Here is how the defaults, 0.1 initial and 1.15 backoff, look:

-c,--health-check-interval- This parameter specifies how often huey should check on the status of the workers, restarting any that died for some reason. I personally run a dozen or so huey consumers at any given time and have never encountered an issue with the workers, but I suppose anything’s possible and better safe than sorry.

-C,--disable-health-check- This option disables the worker health checks. Until version 1.3.0, huey had no concept of a “worker health check” because in my experience the workers simply always stayed up and responsive. But if you are using huey for critical tasks, you may want the insurance of having additional monitoring to make sure your workers stay up and running. At any rate, I feel comfortable saying that it’s perfectly fine to use this option and disable worker health checks.

-s,--scheduler-interval- The frequency with which the scheduler should run. By default this will run every second, but you can increase the interval to as much as 60 seconds.

-u,--utc- Indicates that the consumer should use UTC time for crontabs. Default is True, so it is not actually necessary to use this option.

-o,--localtime- Indicates that the consumer should use localtime for crontabs. The default behavior is to use UTC everywhere.

Examples¶

Running the consumer with 8 threads, a logfile for errors only, and a very short polling interval:

huey_consumer.py my.app.huey -l /var/log/app.huey.log -w 8 -b 1.05 -m 1.0

Running single-threaded with periodict task support disabled. Additionally, logging records are written to stdout.

huey_consumer.py my.app.huey -v -n

Using multi-processing to run 4 worker processes.

huey_consumer.py my.app.huey -w 4 -k process

Using greenlets to run 100 workers, with no health checking and a scheduler granularity of 60 seconds.

huey_consumer.py my.app.huey -w 100 -k greenlet -C -s 60

Consumer shutdown¶

The huey consumer supports graceful shutdown via SIGINT. When the consumer

process receives SIGINT, workers are allowed to finish up whatever task

they are currently executing.

Alternatively, you can shutdown the consumer using SIGTERM and any running

tasks will be interrupted, ensuring the process exits quickly.

Consumer restart¶

To cleanly restart the consumer, including all workers, send the SIGHUP

signal. When the consumer receives the hang-up signal, any tasks being executed

will be allowed to finish before the restart occurs.

Note

If you are using Python 2.7 and either the thread or greenlet worker model, it is strongly recommended that you use a process manager (such as systemd or supervisor) to handle running and restarting the consumer. The reason has to do with the potential of Python 2.7, when mixed with threaded/greenlet workers, to leak file descriptors. For more information, check out issue 374 and PEP 446.

Consumer Internals¶

This section will attempt to explain what happens when you call a

task-decorated function in your application. To do this, we will go into

the implementation of the consumer. The code for the consumer

itself is actually quite short (couple hundred lines), and I encourage you to

check it out.

The consumer is composed of three components: a master process, the scheduler, and the worker(s). Depending on the worker type chosen, the scheduler and workers will be run in their threads, processes or greenlets.

These three components coordinate the receipt, scheduling, and execution of your tasks, respectively.

- You call a function – huey has decorated it, which triggers a message being

put into the queue (Redis by default). At this point your application

returns immediately, returning a

TaskResultWrapperobject. - In the consumer process, the worker(s) will be listening for new messages and one of the workers will receive your message indicating which task to run, when to run it, and with what parameters.

- The worker looks at the message and checks to see if it can be run (i.e., was this message “revoked”? Is it scheduled to actually run later?). If it is revoked, the message is thrown out. If it is scheduled to run later, it gets added to the schedule. Otherwise, it is executed.

- The worker thread executes the task. If the task finishes, any results are published to the result store (provided you have not disabled the result store). If the task fails, the consumer checks to see if the task can be retried. Then, if the task is to be retried, the consumer checks to see if the task is configured to wait a number of seconds before retrying. Depending on the configuration, huey will either re-enqueue the task for execution, or tell the scheduler when to re-enqueue it based on the delay.

While all the above is going on with the Worker(s), the Scheduler is looking at its schedule to see if any tasks are ready to be executed. If a task is ready to run, it is enqueued and will be processed by the next available worker.

If you are using the Periodic Task feature (cron), then every minute, the scheduler will check through the various periodic tasks to see if any should be run. If so, these tasks are enqueued.

Warning

SIGINT is used to perform a graceful shutdown.

When the consumer is shutdown using SIGTERM, any workers still involved in the execution of a task will be interrupted mid-task.

Events¶

As the consumer processes tasks, it can be configured to emit events. For information on consumer-sent events, check out the Consumer Events documentation.